First Lines

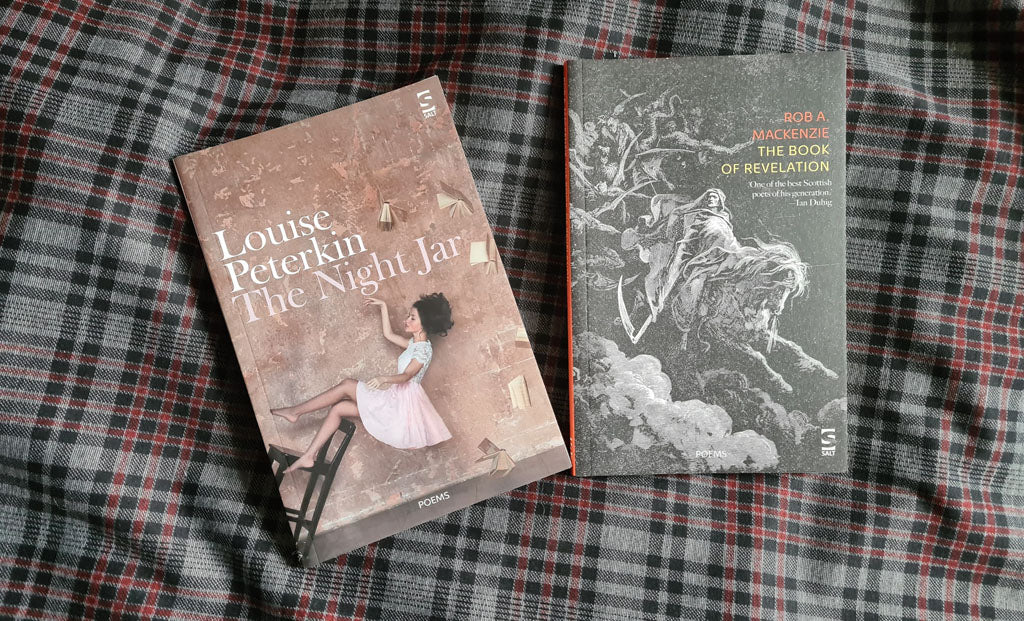

Rob A. Mackenzie and Louise Peterkin in Conversation

Rob A. Mackenzie: The first line of the opening poem in The Night Jar is striking – “Roll up! Big top in view like a yummy mirage”. It’s an invitation (to the circus audience, to readers), but also the word “yummy” stands out, a very unliterary word that won’t often feature in poems. It’s distinctive! It’s got me thinking about opening lines in poems and how important they are. When Cate Marvin writes “Dead girls don’t go the dying route to get known” (‘Oracle’), she has my attention. When Terrance Hayes begins ‘A House Is Not a Home’ with “It was the night I embraced Ron’s wife a bit too long/ because he’d refused to kiss me good-bye”, I’m not going to stop reading.

Louise Peterkin: Yes, The Night Jar opens with an untitled poem, which starts “I open the Night Jar”, but that poem is a prelude, separate from the collection itself. I was inspired by the Anne Sexton collection Transformations, her dazzling interpretations of The Brothers Grimm tales, which has a prelude poem ‘The Gold Key’; it has a "gather in children, let me tell you a tale …" vibe. Then she starts with Snow White. ‘I open the Night Jar’ is my "gather round" introduction. I separated it by having it in italics and not including it in the contents page. When The Night Jar is opened one of the characters bursts out (Sister Agnieszka) and it is lively and fizzy and, yes, the “Roll up” is an invitation to the reader.

The first line in your collection starts like a fairy tale, establishing a purposefully vague time and place – “Somewhere off-calendar, beyond the powergrub annals” is like “Once upon a time, in a land far, far away”.

RAM: That poem looks from elsewhere into the world. What are “powergrub annals”? I haven’t a clue. Intuitively, it felt right and came out of nowhere, satirizing “powergrab” with an image of insect larvae. Also the idea being ‘grubby’. The powers-that-be are observed from somewhere they cannot touch or control. Power, where it lies, how it works, how it can be challenged without mirroring current misuse, is an important theme of the collection.

First lines suggest tone, mood. They can be quiet or high-octane, but not pointless or insipid. Jen Hadfield is good at this – sometime flamboyant first lines, sometimes plain. They make you want to read on.

LP: Jen Hadfield’s sheer joy in language is infectious and almost all her lines feel exhilarating. Her poems never diminish in interest and quality after a good beginning. In fact, she’s almost an exception to the good first line rule! Not that she doesn't have interesting first lines, but I trust her work enough to know what follows will be satisfying and justify whatever the first line holds. See how ‘Still Life with the Very Devil’ develops from the standard first line: “Nothing in the cupboards/ but condiments and liquor// half a red onion with parched corona/ of carmine and violet, madder and magenta”. The poem ends with the astonishing:

The sink is plugged with duckstock.

Dishes stacked like vertebra.

Under the broiler,

turned sausages ejaculate.

You are very playful. ‘Chapter 3’ in the Book of Revelation sequence starts "My emails to a capybara win the Ted Hughes Award". I love capybaras. In response to that poem I have to say, "You had me at capybara". I enjoy how a single phrase or idea, something overheard on the bus, can spark a poem for you. It's like a starting pistol going and then you are off.

RM: I don’t know where the phrases come from most of the time but some are overheard. That one was just a random thought I had about poetry prize culture! You’re right about Jen Hadfield, and I think it’s a strategy – not a conscious strategy, but intuitive. You start off with a deceptively casual first line and then unbalance the reader progressively. John Ashbery is a master at this, setting tone and register with opening lines and then completely undercutting them. Seamus Heaney in ‘Mint’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xc1Wprr-HYA starts with the quiet “It looked like a clump of small dusty nettles/ Growing wild at the gable of the house”. He shifts unexpectedly with a biblical allusion and a declaration of freedom in survival, and then shifts even more dramatically:

Let the smells of mint go heady and defenceless

Like inmates liberated in that yard.

Like the disregarded ones we turned against

Because we’d failed them by our disregard.

That poem switches from a personal memory of a wild garden herb to a universal evocation of political prisoners and all those labelled as agitators, whose hopes, causes and lives have been disregarded by power. You return to that first line and have to read it in a different way.

LP: Wow! That is where the brevity of the poem as an art form can come into play – you can reach the end and then allow your eyes to scan back up to the beginning and start retracing the subtle cues in the language that lead you to the revelation – a beautiful loop!

I do get a kick out of poems whose titles also serve as the first line of the poem. It gives the reader the sense that every word is essential or connected, that the poem has begun as soon as your eyes hit upon the first word; it can kick-start the poem with kinetic, organic energy. An example of this is ‘Every Wednesday’ from GB Clarkson’s extraordinary first collection Monica’s Overcoat of Flesh. The title leads into the lines that follow:

V’s pulling away in torqued autumn light –|

eager foragers off, nosing truffle-rich mulch.

The lines describe the double V of the word “Wednesday” in the title as well as the pattern of the day’s events. The poem expands to a sinister narrative set in either a domestic setting or some sort of communal living space or refuge, I am not sure which. A character initially called V is introduced – later named as “Verity”, who unsettles the dynamic with her brusque opinions and prophesises – opening up a poetic world of syllabary and signs. Once the importance of the letter V is introduced in the first stanza and in the protagonist’s name, you can’t help but be drawn to the v sounds throughout – “devils”, “medieval”, “starved” “vanished” – and the shape of the letter V, pointed like a dagger, tapered to a trap. The final stanza, with its subtle allusions to a split persona reinforce the double V of the W in the title. There it is again – the beautiful loop. Magic! I love what writers like GB Clarkson are doing – testing the limits of where poetry can go.

RM: So, what we can conclude from this is that there is no formula for a good opening line. A first line is apposite because the rest of the poem makes it so, just as the rest of the poem finds its identity because of the pressure exerted by the opening lines. No formula, as always in poetry, but food for thought perhaps?

LP: I’d say so. And we’ve only scratched the surface. I guarantee that I will be reading a collection on the bus tomorrow and discover that incredible first line that I should have mentioned. Anyway, here’s to first lines – they start everything off … poems, imaginations, conversations, blog posts!