Saying Dirty Things in Regional Accents, thanks to James Kelman

by Neil Campbell

I first read James Kelman’s stories in the mid-nineties and, while I hugely admired Kelman from an early stage, I found his work hard going. At that time, I preferred the spare prose of Raymond Carver and also tried to work towards Hemingway’s iceberg principle, where most of what goes on in a story is beneath the surface. I loved Carver back then, but he was a terrible influence on me.

|

|

I’m not sure how I first heard about thi wurd. It was probably via social media. Issue number 3 came out in June 2018. Well, I was late to the party on that. I probably bought it two or three years ago, before it finally sold out. In that issue there is a wide ranging and wonderful interview with James Kelman, and it was reading that interview that finally opened his work up for me. I understood what it was he was trying to do in that densely packed prose of his, and it also revealed a whole new approach to writing fiction, a narrative where voice is more important than plot.

I was unwittingly doing similar things in my trilogy of Manchester novels, where I instinctively tried to just ‘write in a Manchester accent.’ And although this uncomplicated approach worked out fine, I had no real reason to do it, other than a feeling that I hadn’t seen it done anywhere before. Reading Kelman’s interview helped me to understand what he had done in Glasgow, and what I was doing in Manchester.

I’d always wondered why I preferred American fiction; it was because those writers wrote in a voice that captured where they came from, whereas most of all English fiction was written in the King’s English, the imperial language of our rulers. In the same way they ruled a Commonwealth, they ruled the working class. And they did this, in one aspect, through language, the language of the oppressor. Writing in your own voice is a way to escape that. Fuck grammar and punctuation. All that shows is your schooling. Write in the way you talk. Fiction is art, not Creative Writing. Don’t get me started on ‘Creative Writing’. A mate of mine said to me, ‘What’s that, calligraphy?’

There was great controversy when Kelman slipped through the net to win the Booker Prize in 1994. The middle-class publishing elite couldn’t stand Kelman’s novel about a day in the life of a working-class Glaswegian, for them this wasn’t the subject for art, and they made their point by counting the swear words.

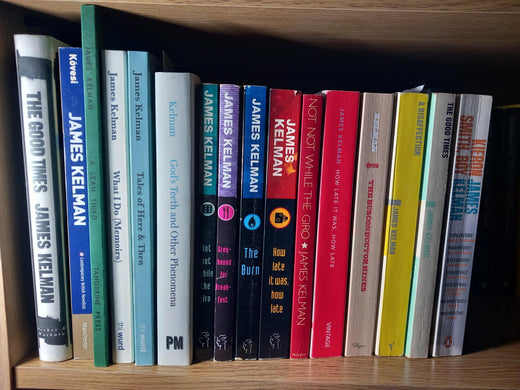

There have been other influences on my latest book, people like Duncan McLean (the skateboard factory story) and all those Rebel Inc press writers from the nineties, like Laura Hird, as well as Hubert Selby Jnr (see The Coat) and legions of other American writers like Larry Brown. But James Kelman is the single greatest working class fiction writer I have encountered. For forty years or more he has been the main man in working class fiction, what we could just call fiction, were publishing not still dominated by the middle class.

This book would not have happened without James Kelman’s example. Thank you for an inspirational lifetime of art, you fucking beauty.

Neil Campbell is from Manchester. He has appeared four times in Best British Short Stories, and his debut novel Sky Hooks was published in 2016. He has four collections of short stories published, and two poetry chapbooks.